Goa Referendum: An analysis of India’s only public referendum on joining Maharashtra or staying independent

Goa Referendum: In 1967, Goa conducted India’s only referendum to choose whether to unite with neighboring Maharashtra or remain an independent Union Territory, marking a unique democratic experiment. The region’s particular cultural-political trajectory was shaped by this public vote, which was formed out of post-liberation conflicts and confirmed Goa’s distinctive character while establishing a precedent against forced language mergers.

Demands for early merger and independence from Portugal

Goa was ruled by the Portuguese until December 1961, when it was freed by the Indian military during “Operation Vijay.” In contrast to the rapid integration of other European enclaves like as Daman and Diu, Goa was immediately under pressure from Maharashtra’s Samyukta Maharashtra Samiti (SMS). As an extension of their ‘greater Maharashtra’ vision, they called for union on the basis of Marathi language links with Goa.

At first, Goa, Daman, and Diu were collectively classified as a single Union Territory by the national government. The “Goa Opinion Poll Committee,” which was founded by pro-merger activists, conducted fictitious surveys and found that 75–80% of respondents supported joining Maharashtra. Delhi called a formal referendum as tensions increased due to rallies, burning, and altercations.

The campaign struggle and the referendum issue

The poll, which was set for January 16, 1967, presented a simple binary choice:

Option 1: The current state of affairs as a Union Territory (distinct from Maharashtra)

Option 2: Maharashtra merger

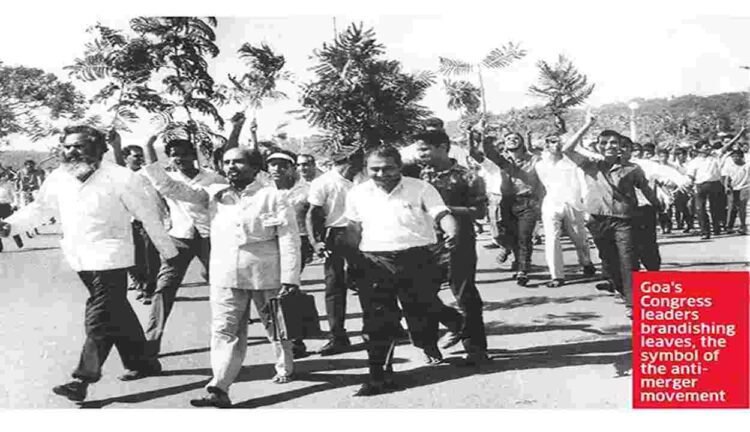

The campaigns were sharply divided. Pro-merger forces highlighted common Marathi culture, casino-free government, and economic advantages. They were supported by Maharashtra leaders like George Fernandes. Dr. Oliveira Gracias and the Maharashtrapanchayatantra Virodhi Mandal led anti-merger Goans who emphasized Goa’s Konkani identity, Catholic tradition, tourist potential, and concerns about losing liberal laws like easier divorce.

Green or black slips put into boxes, making voting easy. Goa’s destiny was decided by more than 5 lakh people, with an 86.2% turnout.

Final triumph for separation

With Option 1 receiving 34.21 percent of the vote (1,72,268 ballots) and Option 2 receiving 14.18 percent (71,464 votes), a 20 percent margin, Goa decisively rejected the merger. Interestingly, a staggering 49.7% of ballots were deemed invalid, which is sometimes taken to mean protest abstentions.

The Status Quo (UT) option garnered 1,72,268 votes, or 34.21 percent of the total, in the most recent poll. With 71,464 votes, or 14.18% of the total, the Merger (Maharashtra) option was chosen. The largest percentage of votes cast—2,50,269—were invalid, accounting for 49.70 percent of the 5,03,001 total. Pro-merger lobbyists were shocked by this result, which contradicted pre-poll polls.

Goa’s journey to independence and the political fallout

Goa remained a Union Territory when Prime Minister Indira Gandhi respected the ruling. The 56th Constitutional Amendment granted it full sovereignty in 1987, making it the 25th state in India together with Daman and Diu as independent UTs. Although the vote put a stop to calls for a merger, it strengthened the Konkani language movement, which resulted in Konkani’s official status in 1987. Additionally, it preserved Goa’s Portuguese-influenced character and fueled the island’s tourist boom.

Legacy: An example of democratic self-government

India’s lone referendum, which demonstrated that popular will prevails over linguistic majoritarianism, continues to be a significant milestone in federalism. It emphasized Goa’s credo, “unique in unity,” and impacted subsequent discussions, like as the statehood of Uttarakhand. The 1967 referendum represents Goa’s unwavering decision for autonomy, even as border tensions sometimes reappear today.